Introduction

Live in Japan for any length of time, and you will come to realise that people tend to take their hobbies seriously, often to the point of excluding all other pastimes. Rare is the mere dabbler; more common is the person who devotes themselves to a single hobby in an attempt to master it. (We’re only exaggerating a little bit.) Somehow, this fits very well with the overall tendency towards specialisation.

If you have a hobby — not everybody does — there is probably a shrine for you. Some activities have already been covered in the ongoing series of strangely specific shrines, such as cooking, or sports like baseball, football, and running. Here are a few more.

Sewing

Sewing is more than the art of mending; it is also to embroider and embellish, to tailor and create. Count yourself fortunate if you enjoy this useful skill! Today, we can buy clothes or pay someone to patch them up, but sewing used to be a fundamental skill in the household, and needles a part of the arsenal of everyday tools.

(Linguistic aside: gender-neutral terms for a person who sews are “sewist” or “sewer” — terribly inelegant.)

Sewing needles don’t last forever. They break, bend, or rust unnoticed until they become unusable. They would be disposed of today without a second thought, but in previous centuries, such needles would be offered to temples or shrines to be enshrined in a ceremony — Hari Kuyō, or the Needle Memorial Service.

As the name suggests, this event honours and expresses gratitude for old sewing needles that can no longer be used. The origins of this ritual remain unclear. One widely accepted theory suggests that it was originally introduced to Japan from China around the ninth century. More mythological origin stories suggest, for example, that it began as a ritual honouring Sukunabikona, the deity credited with teaching humans the art of sewing.

Needle memorial services are traditionally held on 8 February or 8 December, although the date varies in West Japan. 8 February marks the beginning of the new year’s work, while 8 December marks the end of the year’s work, including farming tasks. Women would take a rest from needlework on this day to pay their respects to their faithful needles, while also praying for continued improvement in their sewing skills.

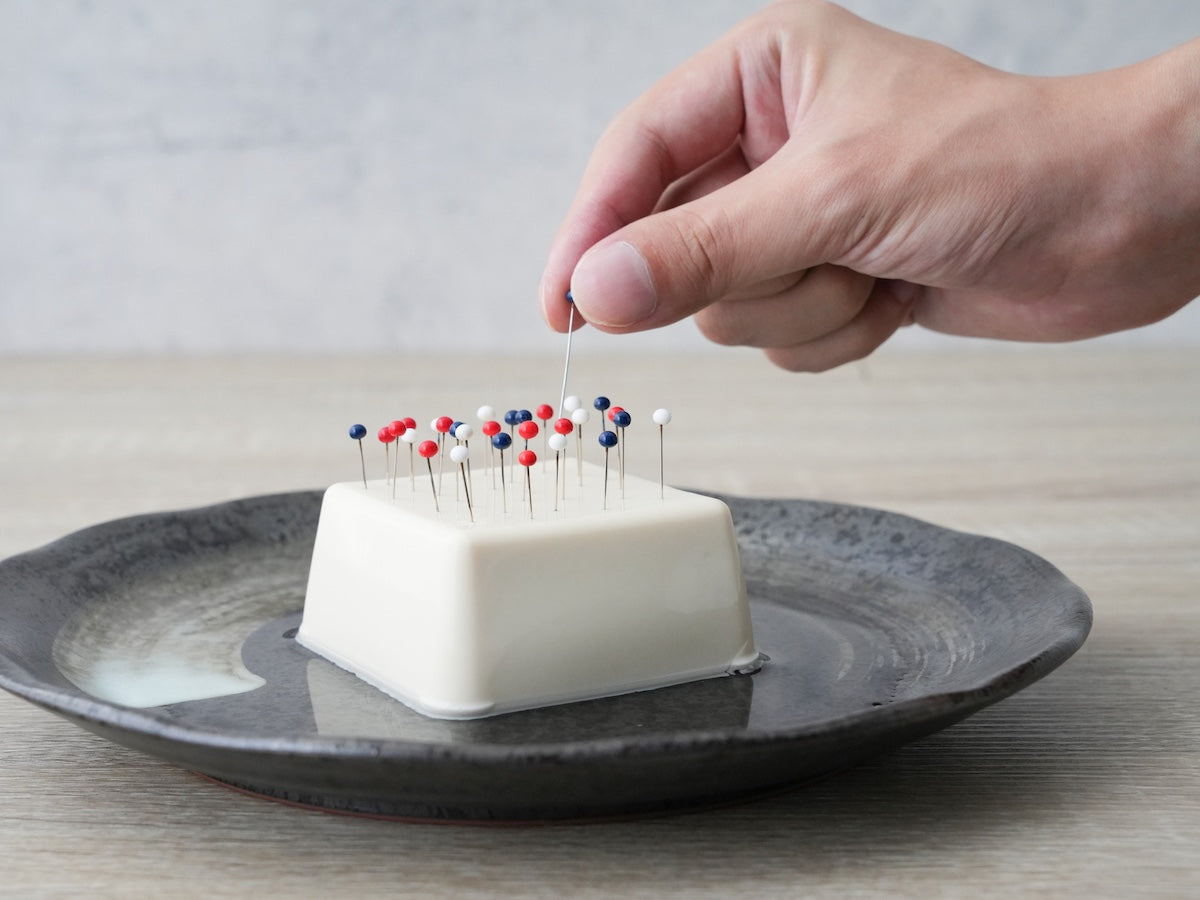

One of the most charming aspects of the Needle Memorial Service is that the needles are memorialised by placing them into a specially commissioned giant block of tofu or konjac as offerings. The idea is that these needles have worked hard throughout their life, struggling with stiff fabrics and tricky stitches, so their final resting place should be somewhere soft. If attending this event, this is a good time to pray for better embroidery skills.

Places in Tokyo that conduct the Needle Memorial Service include Shōju-in Temple in Shinjuku Ward, Teppozu Inari Shrine in Chuo Ward, Hatonomori Hachiman Shrine in Shibuya Ward, and Awashima Hall in Taitō Ward; elsewhere in Japan, there’s Egara Tenjin Shrine in Kamakura, Itsukushima Shrine in Kobe (not to be confused with the one in Hiroshima), and Inui Shrine in Kyoto.

Inui Shrine, located on the precincts of Mizushi Shrine in Jōyō City, is particularly well-loved by those involved in fashion, sewing, cosplay, embroidery, dressmaking, and more. Enshrined here are Ōnui and Onui, the deities of sewing clothes; they were believed to have sewn garments for the legendary Emperor Sujin (allegedly 148 BC - 30 BC), and for their troubles were collectively given the title of Kinunui (now pronounced Inui). The shrine’s Needle Memorial Service is held on 29 April, and attended by members of the Association of Traditional Japanese Dressmakers.

We leave you with one last place for sewists. Nuidono Shrine in Fukuoka claims to be the first dedicated to the deity of sewing, enshrining four women — Ehime, Otohime, Kurehatori, and Anahatori — who were invited from the state of Wu (present-day China) to introduce textile and sewing techniques to Japan. This supposedly took place during the reign of Emperor Ōjin (201 AD - 310 AD). Out of the four, Ehime remained at the request of the Munakata goddesses — daughters of Amaterasu — to teach advanced dyeing, weaving, and sewing techniques.

While the telling of this tale has an air of myth around it, the idea that these techniques were introduced from China via trade is entirely plausible. The term ‘Nuidono’ 縫殿 also refers to an office in the Ritsuryō period — roughly late seventh to early tenth century — that managed women who worked in the Imperial domicile, and supervised the production of imperial court garments for aristocrats of high rank.

Paper and papermaking

It’s not often that there’s a completely unique shrine in Japan, no matter what many of them might claim — but Okamoto-Otaki Shrine in Echizen City, Fukui Prefecture, does indeed have the distinction of being the only one in Japan dedicated to the deity of paper and papermaking.

Echizen is often described as the birthplace of washi paper. It’s tough to say if that’s true, but it does have over 1,300 years of papermaking history, and the washi produced there was highly sought after by the Imperial court.

The legend surrounding the origins of papermaking here tells of a mysterious woman who descended to the valley from the upper reaches of the Okamoto River. She told the villagers that they had little land to farm, but that they were blessed with abundant clean water, and would prosper if they turned their hands towards making paper. Thus saying, she taught them the craft of papermaking. As she had come to them from upstream, she was deified and venerated as Kawakami Gozen — literally, Lady from the Upper River.

Papermaking isn’t the most common hobby around, but it is one that’s surprisingly accessible and easy to do at home. Okamoto-Otaki Shrine is well worth the visit not only to give thanks (whether for the existence of paper, or for Echizen’s washi industry) but also to check out its complex and stunning architecture.

Fishing

As befits an island nation, many shrines and temples across Japan offer blessings for abundant catches, fair weather, and maritime safety. However, these aren’t exclusive to those who fish for a living — amateur anglers and people involved in recreational fishing are catered to at shrines as well, in the form of piscine lucky amulets. Some of the deities associated with fishing and general ocean-related affairs are Ebisu, patron of fisherfolk and tradespeople; Ryūjin the Dragon King, deity of the sea; and Suijin, the Shinto divinity of water and guardian of fisherfolk.

The first stop for Tokyoites who fish should be Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in Koto Ward. A landlocked shrine around a kilometer inland might seem a curious choice for fishing amulets, but the neighbourhood was historically a small coastal island before successive city governments carried out land reclamation projects. Their omamori offer blessings for safe fishing trips and bountiful catches. As a bonus, they’re waterproof — ideal for being attached to gear bags, cool boxes, and the like.

Those wishing to pray to the powerful Dragon King in particular can visit Honkōji Temple in Chiba, Kuzuryū Shrine in Kanagawa, Tanashi Shrine in Nishi-Tokyo, or Ryu Shrine in Chiba.

Located in Yaizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Nahe Shrine has watched over fisherfolk for around 1,500 years. There was no shrine building in the beginning, as the mountain in the area itself served as the main sanctuary for the deity.

Nahe is most notable for its Uramatsuri — literally, ‘Bay Festival’ — where the shrine priests pray and offer blessings for abundant catches. According to the shrine, ‘ura’ was originally written with the character for ‘divination,’ suggesting that this was a festival for prophesying catches. Records suggest that the festival was a tremendously lively affair, with ‘mountainous heaps’ of skipjack and bluefin tuna offered to the deities alongside casks of sake.

Nahe Shrine’s lucky amulets come in the following fish varieties: black sea bream, Japanese rockfish, flatfish, sea bass, horse mackerel, skipjack tuna, and squid. Most of them seem to be sold in limited quantities, and there are past designs featuring swordfish, splendid alfonsino, and red sea bream that have already sold out. If you can’t make it to the shrine, there’s always the mail-order option.

For another proper seaside fishing shrine, try Shikaumi Shrine at Shikanoshima in Fukuoka City, dedicated to three deities of the sea, collectively known as the Watatsumi Gods. The shrine’s amulet features a fishing hook and fish inside a transparent bottle, and apparently is popular enough to sell out around New Year’s Day when everyone makes their first visit of the year to the shrine.

Shogi

To most people in Sendagaya, Tokyo, Hatonomori Hachiman Shrine is probably just the neighbourhood shrine — a quiet, pretty place to take a breather from the work day. But to shogi (Japanese chess) enthusiasts, Sendagaya is the heartland of the Japan Shogi Association (JSA), and the shrine its divine office.

The shrine itself doesn’t seem to have a long history with the game. Its association seems to have begun in 1986, when the then-President of the JSA donated a shogi piece made from lacquered zelkova wood, standing approximately 1.2 metres tall and inscribed with the characters for ‘king’ 王将. That same year, the JSA and Hatonomori Hachimangu collaborated to build the Shogi-dō, a hall that would house this piece.

Every January, the JSA holds a prayer ceremony at the shrine’s Shogi Hall, attended by shogi enthusiasts of all stripes. This is a special occasion, as this is the only time of the year the doors of the Hall will be opened, and for only three hours. Following this, the shrine then hosts the New Year’s Opening Game, where members of the public take turns playing one move each against a professional player.

Naturally, the shrine offers merchandise in the form of shogi-themed lucky amulets that feature a design that depicts the decisive ‘checkmate’ position. These are for improving and developing one’s shogi skills, but also to pray for victory in competitions of all sorts.

Carpentry

Some people simply do not have a knack for DIY; don’t ask me how I know. (Spoiler: it’s lived experience.) Handy people with a talent for woodworking and all-round DIY have probably been blessed by the gods. Specifically, the protectors of carpenters and craftspeople.

The deities in question are Taokihoi and Hikosashiri, who are associated with measuring and building shrine structures and implements — or more broadly speaking, architecture and carpentry. They often appear as a pair. (Okuninushi doesn’t count here as he is a kami of nation-building, rather than more tangible things like house foundations.) According to one of the founding myths of Japan, these two deities were tasked with constructing a sacred hall, as part of the plan to lure Amaterasu out from the cave in which she had hidden herself.

DIY enthusiasts in Tokyo have the option of visiting Araka Shrine, a subsidiary shrine on the precincts of Ishihama Shrine in Minami-Senju. This small shrine was established in 1779, and has since been a well-loved shrine for devotees who work in the construction industry. Curiously enough, it’s not normally accessible for worship as it is located behind the main hall. Araka Shrine used to be located outside Ishihama Shrine, but was destroyed by arson and relocated inside by repurposing one of the existing Hachiman shrines inside. As such, the worshipper needs to make an advance reservation by phoning ahead.

Alternatively, one can also visit Awa Shrine in Chiba (also great for money luck), Nakoshiyama Shrine in Chiba, and Teono Shrine in Shimane to pray to these two deities. Nakoshiyama in particular is especially revered by Japanese carpenters and builders nationwide, and holds lively festivals in July and November.

Written by Florentyna Leow