- What Are Yokai and Why Do They Love Your House?

- Yokai Habitats: Where the Wild Things Are

- Thresholds and the Thrill of the In-Between

- Akaname: Scum-Licker

- Mokumokuren: Eyes on Sliding Doors

- Yanari: House Rattler

- Karakasa Kozo: Umbrella Boy

- Makuragaeshi: Pillow Flipper

- Zashiki Warashi: Parlor Child

- If the House Feels Empty, Tell 100 Tales

What Are Yokai and Why Do They Love Your House?

In Japan, the supernatural goes by a few names and one of them is yokai, sometimes translated, with more drama than precision, as Japanese folk monster.

The term took the scenic route over. Originating in China, it was in use in Japan by the 8th century: it pops up in the Shoku Nihongi text, where the imperial court is recorded as holding a purification ritual because of a yokai sighting.

Despite this early appearance, the term didn’t really catch on until the 20th century, when Yanagita Kunio - the father of Japanese folklore studies - dusted it off and used it as a catchall label.

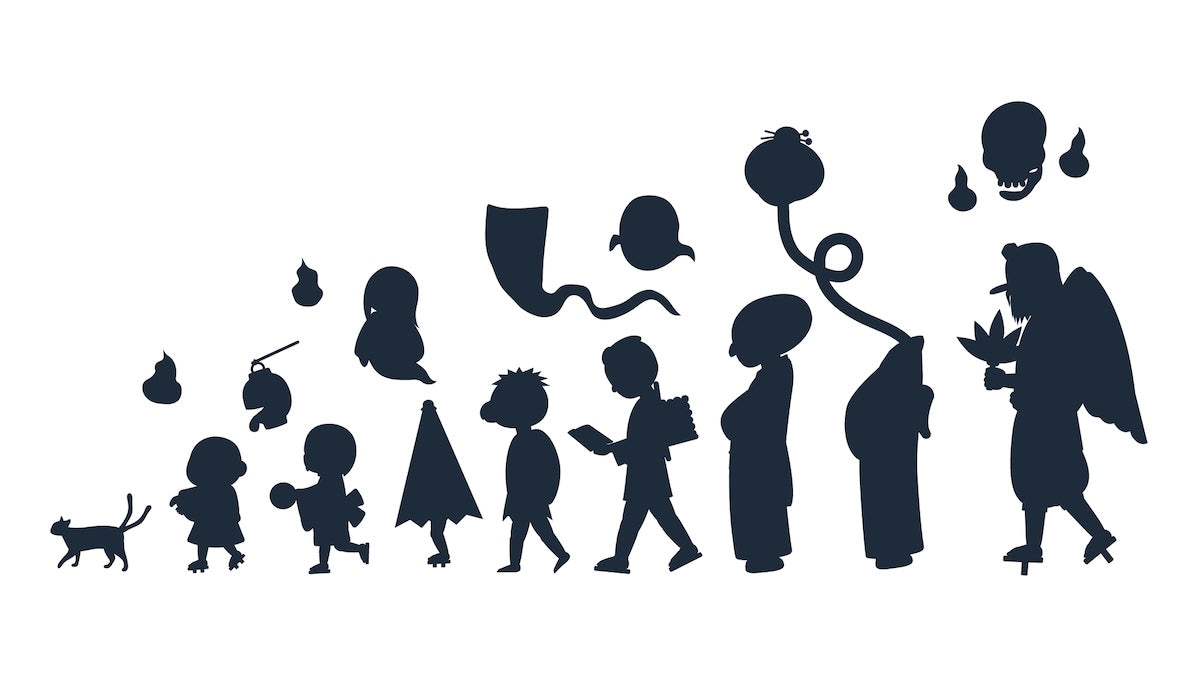

Manga artist Mizuki Shigeru then made sure it stuck, populating his GeGeGe no Kitaro series with folklore oddballs and turning them into pop culture icons.

Before the word 'yokai' (妖怪) came into vogue, the term of choice was 'bakemono' (化け物), literally 'changing thing', a description favored in the Edo period for the otherworldly.

Like 'yokai', it was a category with plenty of elbow room, making space for everything from terrifying oni to sly fox spirits to household objects that decided, after a century of service, to sprout limbs and opinions. Most people would exclude ghosts from this category but might include gods. Why? It's...complicated.

Though 'monster' is a common English translation for 'yokai', it can be misleading. Yes, some are dangerous - very dangerous - but others are more prankster than predator and some are simply…odd.

The unifying trait is transformation and that shiver down the spine when the familiar slides into the strange.

This could be a wandering light with no apparent source or an eerie sound in the next room - was that something shuffling over the tatami? Or someone? A yokai might be born in that moment when you notice something off but can't plonk it into a cognitive box.

Humans everywhere, not just in Japan, have a habit of giving unexplained events a supernatural face. Across Japan, yokai have served for centuries as a shorthand for 'there’s something strange afoot and it demands a story so we can feel better about it'.

Even if we can't control the situation, with a tale to explain it, we can at least be entertained.

Yokai Habitats: Where the Wild Things Are

Like people, yokai gravitate toward environments that reflect their personality. Often, this means the natural world - unpredictable, untamed and free of wi-fi.

They lurk in oceans, rivers and swamps (watch your step; a kappa may have plans for you), but seem especially fond of mountains and forests.

Sometimes they descend from their strongholds to mingle with humans. If you suspect the friendly stranger you just met is actually a fox spirit or tanuki, check for the tail that they can never quite hide.

But what about the yokai who turn up inside the home - far from any mountain - and act like they’re there for more than a short visit?

One of the defining traits of yokai is their love of the in-between. As exemplified by the tengu, they’re not quite human and not quite animal; sometimes they harm, sometimes they help.

So it’s no surprise that they favor landscapes and situations that are neither here nor there: a mountain pass between villages, perhaps, or a river between two fields. A dusky road - a borderland of space and time - is naturally a favorite haunt.

Thresholds and the Thrill of the In-Between

Solid as they may seem, houses are built of thresholds where we shift between states: waking and sleep, indoors and outdoors, this room and the next.

No wonder that yokai take up residence, with all these boundaries - doors, ceilings and that nightly portal to the dream world: your pillow.

Old Japanese houses, in particular, are a paradise of in-between spaces: the draft along the engawa verandah, the shadow beneath the tansu chest, that gap between fusuma panels.

Spend the night in a machiya or a farmhouse and you may feel watched. Something flickers at the corner of your vision but when you turn to look, it’s gone. If this happens, don’t panic. Just think of it as a cultural episode.

Akaname: Scum-Licker

This creature slinked into print when it appeared in influential ukiyo-e artist Toriyama Sekien’s Gazu Hyakki Yagyo, or The Illustrated Night Parade of 100 Demons.

This 1776 bestiary depicts it as a long-tongued, claw-footed humanoid lurking near a bath. But the concept is older - a yokai called akaneburi turns up almost a century earlier in a 1686 work. The earlier name means much the same thing: dirt licker.

Edo-period sources say akaneburi spontaneously generates from accumulated filth and feeds on the very muck that spawned it. In the 20th century, stories describe akaname as haunting old bathhouses and abandoned mansions, sneaking in at night to give the bathtub a once-over with its oversized tongue.

It doesn’t attack people but its mere appearance is enough to put anyone off their evening soak. The solution is simple: clean the bath.

Final tip: prevention is not only better than cure; it's also considerably less slimy.

Mokumokuren: Eyes on Sliding Doors

First recorded in Konjaku Hyakki Shui, the 1781 instalment in Sekien's blockbuster yokai series, mokumokuren is exactly what it says on the label: eyes sprouting in shoji paper screens. Not just one or two but eyes and more eyes in almost every panel, as if the entire house has signed up for a staring competition.

The tale didn’t stop with Sekien. More than a century later, Mizuki Shigeru redrew the yokai, adding a panicked man fleeing the scene.

The artist also retold the story of a lumber merchant from Edo - pre-modern Tokyo - who traveled to north-east Japan on business.

Unable to find a place to stay, he decided to sleep in a deserted house. The hour was late and the shoji had holes. But when eyes appeared, he wasn't at all frightened.

With typical Edo chutzpah, he plucked the eyes out one by one and sold them to an eye doctor back in the city: an early instance of the supernatural becoming part of a supply chain.

Final tip: they’re harmless but staring contests are discouraged.

Yanari: House Rattler

Unlike some of Sekien’s inventions, this yokai predates the Edo period and can be found in rural Japan’s oral traditions.

When your house is hit with yanari, walls shudder, beams creak, furniture shakes but there’s no earthquake, no typhoon and no explanation.

In Sekien’s Gazu Hyakki Yagyo, the culprit is clear: a small, demon-like yokai gleefully rattling a wooden building.

Even now, unexplained creaks and groans in a house are sometimes called yanari - house noise - especially in a new house where the timber hasn’t fully settled.

Seasonal shifts in temperature and humidity can set the structure rumbling though, in severe cases, the noise can turn into the uproar of a legal dispute between the builder and owner.

Final tip: before blaming the supernatural, check the building.

Karakasa Kozo: Umbrella Boy

The poster creature of the object-based yokai world, it's most often depicted as a single-eyed paper umbrella, hopping on one leg with a tongue lolling out.

Sometimes, it has two arms, sometimes, two eyes and, in a 19th-century portrait, it ditches the pogo-stick routine and sprouts two legs instead.

This yokai draws life from the Japanese tendency to anthropomorphize even inanimate household objects. The creature's family tree stretches back to medieval picture scrolls, where it appears as a humanoid with a folded umbrella balanced on its head.

The one-eyed, one-legged design that we know today shows up in Edo-period paintings and became a regular on ghost-themed karuta cards from the Edo through the Taisho periods.

While many inanimate objects - lanterns, kettles, musical instruments - have gained yokai status, the humble umbrella has somehow become the star.

Final tip: be careful not to forget your brolly somewhere - you don't want it hopping home and traumatizing the neighborhood.

Makura-gaeshi: Pillow Flipper

Makura-gaeshi is the yokai equivalent of a sleep disruptor.Said to creep up to your pillow in the dead of night, it either flips it over or swaps your head and feet around. The earliest stories date from the Edo period but the mischief continues in modern times.

Its appearance is unclear though it’s sometimes described as looking like a child. In the Tohoku region, pillow-flipping is often blamed on the zashiki warashi, a child-like house spirit.

Folklorist Sasaki Kizen recorded tales from Tono where sleepers would not only find their pillows turned but also feel mysterious pressure on their bodies or wake to find tatami mats lifted, tiny footprints left behind.

Pillow pranks aren’t limited to homes. At Daichuji, a temple in Tochigi prefecture, there’s a room called the Makura-gaeshi no Ma, where a traveler once slept with his feet toward the temple’s principal image. By morning, his head was facing it instead.

There’s a deeper, spookier layer to all this. There's an old Japanese belief that the soul leaves the body during dreams, and turning the pillow while someone sleeps could prevent the soul from returning - a one-way ticket to the afterlife.

This may have some connection with the kita-makura, or 'north pillow', taboo: sleeping with your head to the north mirrors the position of the historical Buddha at the time of his death. Since that orientation is associated with funerals, it’s generally avoided, lest you accidentally invite death to join you for a nap.

Over time, the soul-separation angle faded from popular imagination and makura-gaeshi’s antics came to be seen as mere mischief. Still, if you wake up with your pillow flipped and your feet where your head was, don’t be so sure it was just a restless night.

Final tip: if you wake up turned around, don’t panic - just check whether your new sleeping position brings you closer to the coffee.

Zashiki Warashi: Parlor Child

A sighting of a zashiki warashi can mean one of two things: you’re about to become rich - or you should start downsizing.

Associated with Iwate prefecture in the Tohoku region, these household spirits generally look like children aged three to fifteen, with red faces and bobbed hair or shaven heads.

Zashiki warashi specialize in high-energy mischief. They leave little footprints in the ash and make noises that sound like spinning wheels or kagura sacred music. At bedtime, they might straddle your futon, flip your pillow or simply keep you awake with pranks.

They also have a more benign side, befriending children and, in the case of the Hayachine Shrine zashiki warashi, tagging along with visiting worshippers to teach local songs to children in far-off places.

Custom says you can attract one into a new home by burying a golden ball beneath the floor during construction. But once they’ve moved in, the stakes are high: a house with zashiki warashi will prosper but one they abandon is headed for ruin.

The Tono Monogatari folklore collection is full of cautionary examples. A child from a wealthy family thought it would be a good idea to shoot their zashiki warashi with a bow and arrow. The spirit left and the family’s fortune crumbled.

Another tale tells of a household whose members died of food poisoning shortly after their zashiki warashi moved on.

Moral of the legend? Befriend them, offer them treats and never turn violent even if you've had a scare.

Final tip: if a rosy-cheeked girl starts playing sacred music in your parlor, let her.

If the House Feels Empty, Tell 100 Tales

Still no sign of any supernatural entities? Experiencing FOMO of the paranormal kind? There's a ritual you can perform: Hyaku Monogatari, the gathering of one hundred tales.

Light a hundred candles at night. Tell a spooky story after each, snuffing a flame as you finish.

By the last tale, the room will be in near-darkness and when you take a headcount, there may be one more person than when you began the storytelling.

If that happens, you won’t need to invite them - they’ve already moved in. And those shadowy figures you once saw at the corner of your eye? They're ready to appear in Technicolor.

Written by Janice Tay